I'm passionate about filmmaking, says Mahmood Ali-Balogun

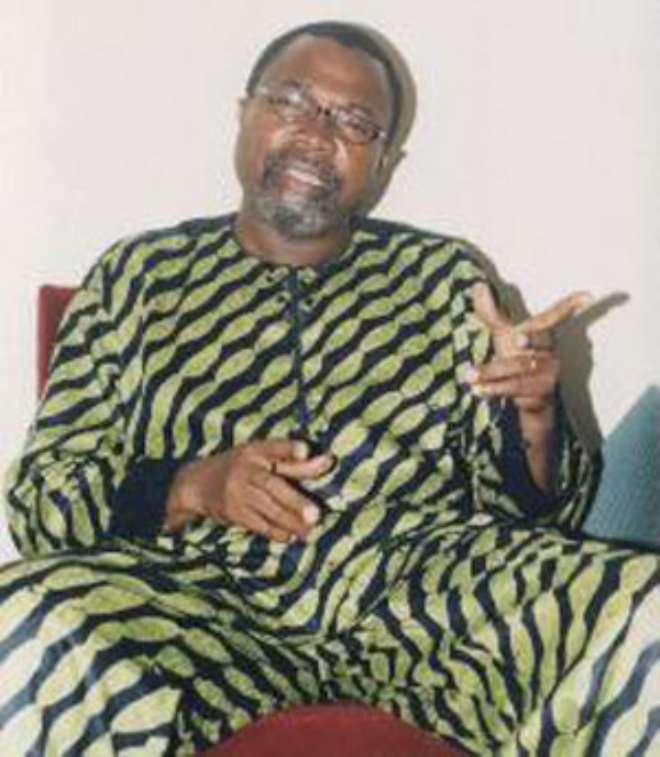

IN this encounter with OJI ONOKO, the former President, National Association of Nigerian Theatre Arts Practitioners (NANTAP), Mahmood Ali-Balogun, who just turned 50, recounts an unusual life and counters the claim that he is not a mainstream director

"WHAT do you mean by mainstream?" He retorts. "Main stream because I'm not doing movies and all that?" There is no anger in his voice. Not even a rise in the pitch. Seated opposite you this Monday afternoon in his Surulere, Lagos office, the air-condition whirring, all he is doing is respond as coolly as possible to a question that could have riled any other person. However, Mahmood Ali-Balogun, former President, National Association of Nigerian Theatre Arts Practitioners (NANTAP), during whose tenure NANTAP recorded phenomenal growth, is not just anybody.

He grew up in the Sabon Gari area of Kano and mixed freely with Igbo boys as well as Hausas. "I went to primary and secondary schools in the North," he recalls. "Life was quite easy. You could move around and do anything you wanted. As kids we grew up in a very nice environment". His father had three wives but this rubbed off positively on him as they lived as one big family even though the children were from different mothers. "We didn't have siblings' rivalry that people say that they have in most families, "he says, "You respected your seniors, your juniors also respected you. That was the kind of discipline that my father instilled in us. With my mum, she was the senior wife and everybody respected her".

It was a modest family. The father, an automobile mechanic was quite literate while the mother who did not have any formal education, engaged in selling food and other articles. The young Mahmood usually assisted the mother in her trade and at other times went to the father's workshop to equally help out. The chores were well spelt out for the children. His was to wash the father's car in the morning; some cleaned the house and others washed the plates. These were religiously done before setting out to school. When they returned, they carried out whatever responsibilities were assigned to them. "It was wonderful" he says. "My father and mum ensured we got the best they could offer. We didn't lack".

There was even indulgence. One of the places the father took the children for sight seeing was Kano Airport (now Aminu Kano International Airport). The aero plane fascinated the young Mahmood and he very much wanted to be not just a pilot but also an aeronautic engineer. To give vent to his desire, he took the study of science very seriously at the secondary school, Ahmaddiyah Secondary School. His dream only came apart when the school could not be accredited to offer science at the school certificate examinations because the laboratory was found wanting. It was no surprise, that Mahmood became one of the students who protested the lapse.

Another place of interest the father took them to was the cinema where they watched the plays of Herbert Ogunde, Baba Sala, and Ade Love when the producers came calling in Kano. The plays excited him greatly that at other times, he would sneak out to other cinema houses in Kano notably Queen and Eldorado to watch American films, Indian films and Chinese films on his own. Unwillingly, the seed of show business had been sown in him.

Still, he rued at his school for truncating his career as a pilot. His fascination then changed to law. So he proceeded to the Federal College of Arts and Science, Sokoto, for his Advanced Level training. But fate played a trick on him. He was expelled from the school! "I partook in the Ali Must Go protest then in Sokoto", he recalls, "When the increase came, it affected not just the universities but the federal schools then. I was the social secretary so to speak. The authorities made sure that some of us didn't get back".

He returned to Kano sudden and sullen. Some of his classmates had since proceeded to the university and here he was without an iota of what to do next. He took up a job with Federal Department of Agriculture which neither challenged nor interested him. Now semi independent, he continued his soiree at the Kano cinema halls, the films serving as purgation. So when one of his friends, Awan Ankpa already studying Dramatic Arts at the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) suggested to him to put in for the course, he was only too happy to oblige. Suddenly the scales fell off him. He pulsated with joy as he filled the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board's (JAMB) form for Dramatic Arts. He was going to study the course and major in filmmaking, he assured himself when he gets the admission. And he did.

His years as President, National Association of Nigerian Theatre Arts Practtioners (NANTAP) have been referred to as the glorious era. He is modest in accepting this. "When you refer to it as glorious era, I appreciate it," he says. "But it wasn't just Mahmood. It was the collective of people including you who had vision as per uplifting the profession - the theatre, the motion picture industry that was nascent then. We were then fresh from the university and we wanted to shed the toga of never-do-well because we all knew what we went through even within the university system to get out. When we came out and saw that our profession was seen as such that can be kept at the back-waters we felt we needed to do something about it. Hence the emergence of NANTAP. Yes, Mahmood was at the helm of affairs, if he didn't have the right type of people to work with, the glorious appellation would not have been there. We were very committed even without the kind of resources that organizations have these days."

But why is he no longer gracing the screen and stage these days as an actor? "I wasn't a trained actor", he confesses. "Even though in the process of being a filmmaker in the Dramatic Arts Department, you also train as an actor along the line. I'm a trained film maker. My core focus was to be a motion picture practitioner which is what I specialized in - Film making and TV production... My days as an actor was a learning curve for me, to prepare me for what I'm doing today."

So what is his reaction to criticisms by some film practitioners that he is not a mainstream director? He adjusts his seat and answers: "It depends on what you mean by mainstream." He clarifies further, "I think what people mean by mainstream is what is happening in Nollywood or may be on TV. One area I have specialised in is that of documentary film making. It is one area that I have done quite a lot. My works are there to speak for me". His face now creases into a smile. "You see, movie making is my passion. And I've got to get the right resources to do the kind of movies I want to do." So, is it about the passion or the money not being right? "It's the passion", he replies. "It's not about the money not being right. The passion is that you want to do it right, you want to do it correctly to the best of your ability. So I must get the right resources at my disposal for me to do that". And perhaps to prove his critics wrong he is at present working on a film which by Nigerian standard is big budget - N60 Million. "I believe God, it's going to be a water shed", he says.

His verdict on the present state of film making in Nigeria is rather harsh. "You see, film making in Nigeria has been brought down to the subsistence level. People now are making film just to put bread and butter on the table. These are the people they call mainstream film makers," he charges. "No, filmmaking is filmmaking whether you do it as documentary, whether you do it as feature, whether you do it as animation".

He is not done yet as he lays down what filmmaking should really be. "You see, filmmaking is not about how many you made. It's not about how long you have been doing it. It's about how well you are doing whatever you are doing and the quality of what you have churned out. My documentaries, I make bold to say, are exposed all over the world. That's why I'm privileged to be invited to places here and there all over the world. The two films I've done, one short, one major speak for themselves and my documentaries."

He then turns to his interventionist role in filmmaking in Nigeria. "Some of us have been involved in getting things done professionally. Putting the right structures in place in terms of professionalism; the kind of people who practice; the codes and ethics of practice; getting people properly trained; advocating for such institutions or even getting involved in the area of funding, distribution and all that. Even with that, if you say I'm not mainstream, so be it".

He laughs now as you ask him how he feels at 50 years of age. "I definitely don't feel it", he says. "Only that the grey in my hair particularly the ones on my head are getting more and I'm beginning to think and know that I'm really 50. You know, I used to deceive myself before with my beard's look... it's something about my family that most of us, our beard gets grey before we get old". He continues, playing with the grey beard with the right hand. "I'm still Mahmood. I still feel strong. I thank God that has kept me thus far".

Any regrets? His answer is a stout no. "I take each day as it comes," he says. "Not that I don't plan, but I take each day as it comes. What of his legacy? "The legacy one can enshrine is not the number of houses you build, not the money you are leaving behind, not the number of children but how in your own time, you affected lives in whatever way," he explains more like a teacher to a student. "That is the only enduring legacy one can leave behind. And I look forward to a situation whereby people would say, ah, Mahmood did this, Mahmood did that, Mahmood made that to happen. Affected lives for the better".

So does he feel fulfilled? He ponders the question. "Fulfilled?" then he says in a modulated voice, the actor in him coming to the fore. "Not yet really. There's a lot to be done. One, on the perspective of the industry, my industry is still unregulated. It is still an all comers affair, so the level of professionalism, the level of putting the right structures in place for people to enter the industry and make a living off it is not there. With that not being there, I don't think I feel fulfilled. On a personal level, as a child of God, there's a lot that is yet to be done in the society. There are so many people out there who are still in need of salvation, who don't know about Christ. So we still need to do a lot to bring the knowledge of Christ to people and to affect the way they live. There are people who can't afford a meal a day. I can't say I'm fulfilled because there's much to be done in the society..."

Latest News

-

"If You're For Me, I Am For You" - Cubana Chief P

"If You're For Me, I Am For You" - Cubana Chief P -

"3 Days To Go" - Femi Adebayo Urges Fans To Get S

"3 Days To Go" - Femi Adebayo Urges Fans To Get S -

"Stop Asking Me Questions About Speed Darlington"

"Stop Asking Me Questions About Speed Darlington" -

"Benue Is The Most Underdeveloped State I've Ever

"Benue Is The Most Underdeveloped State I've Ever -

Stan Alieke Urges Young Professionals To Take Lin

Stan Alieke Urges Young Professionals To Take Lin -

Chizzy Alichi Teases Fans With Baby Reveal, Promot

Chizzy Alichi Teases Fans With Baby Reveal, Promot -

"I'm Not Wearing Makeup From July 4th Till Decemb

"I'm Not Wearing Makeup From July 4th Till Decemb -

"Stop The Challenge Of Mocking Kids With Down Syn

"Stop The Challenge Of Mocking Kids With Down Syn -

Regina Daniels Celebrates Sons As They Mark Birthd

Regina Daniels Celebrates Sons As They Mark Birthd -

Speed Darlington Threatens To Sue NAPTIP For Defam

Speed Darlington Threatens To Sue NAPTIP For Defam