Why Nollywood hardly reflects Nigerian literature

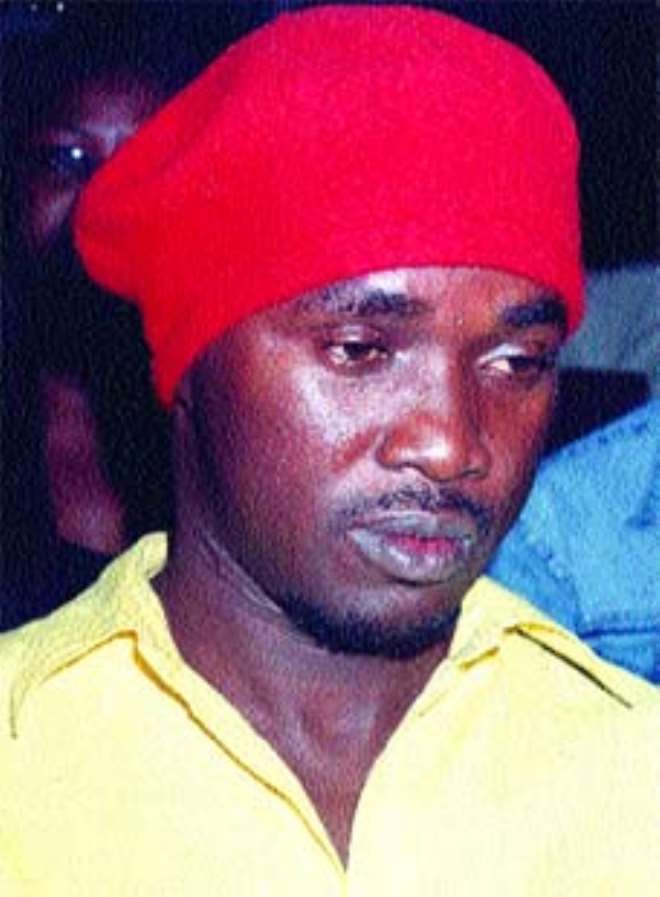

Ebereonwu, ace scriptwriter

Ebereonwu exudes an enigmatic aura that either tickles or revolts. Just like the fiery critic and renowned scholar, Chinweizu, who has no other name, he doesn't either.

Ask him why, and he tells you he likes it that way: authentically African. A poet, playwright, film director actor and one of the most sought-after scriptwriters in Nollywood, Ebereonwu relishes the best of both worlds, and his enigma is enhanced by his outlandish dress code that includes a beret worn at a haughty slant.

Early to bed, early to rise – goes the rhyme. Ebereonwu went to the bed of creativity early and rose early to fame. At fourteen, he had written his first creative work, a play. Two years later, he had started writing for NTA, Aba. Besides, he was the Athol Fugard of an amateur theatre group in his locality.

With this flying start, he knew where his bread was buttered; hence, the choice of English literature as a course of study at Ahmed Bello University, Zaria.

His oeuvre include Suddenly God was Naked, a collection of seventy poems (1995), a drama, Cobweb Seduction (1995), and two other collections of poems, The Insomniac Dragon (2000), and Unpublishable Poems (2004); while another play, Bread of Paradox, is on the verge of publication.

Within the last three years, the multitalented writer has done more than thirty film scripts for Nollywood, Nigeria's developing movie industry, ranked next to American Hollywood and Indian Bollywood in terms of output. Some of the notable films by Ebereonwu include King of the Jungle, Intruder, Fishers of Men, Friends & Lovers, Discord, Bandit Queen, Crazy Passion, Tears for Nancy, and Piccadilly.

The business of scriptwriting for most Nigerian practitioners in Nollywood is not as thriving as it is in the West or India. The ones who make it are the established writers.

Beginners walk through a tortuous path to market their scripts. Compared with other artistes in the industry, the Nollywood scriptwriter is the 'Nathy' in The Village Masquerade opera who goes for the crumbs. While an Nkem Owo, aka Osuofia, or a Jack Orji would take nothing less than five hundred thousand naira to appear in a film, and while the diminutive Aki and Pawpaw would take nothing less than four hundred thousand naira for a role, an average scriptwriter sells his script for a hundred thousand naira.

Ebereonwu and few others are the exceptions. From a meager twenty-five thousand naira, which he sold his first script, his marketing value has appreciated to three hundred thousand naira for a script. Recently, he sold a script at three hundred and fifty thousand naira entitled Banned in Nigeria – "the one Gabrosky [a popular Nollywood producer] is producing now," he informs Sunday Sun at Kingstine-Jo eatery, Ikeja, where he hangs out to watch premiership matches at weekends.

After a sip of Schweppes, he speaks in a stammering monotone about the script's content: "It's a controversial one and it centres on recent wrangling in the pulpit by some leading Christian pastors."

Industry watchers have decried the rate at which Nollywood storylines follow a bandwagon slant. It is either an occult story or a love story. The actors and actresses are often stereotypes, with characters as the pastor, the native doctor, the madman, the wicked mother-in-law, the nagging wife, the ritual businessman, the playboy, the harlot, the born-again, etc. appearing repeatedly. Often people wonder whether the marketers, who unfortunately call the shots in Nollywood, are the ones dictating the content.

"Everybody determines it," says Ebereonwu. "Sometimes a marketer has an idea of the type of script he wants based on the prevailing market demand.

A marketer may approach you to write an occult story because somebody else has done it and it's moving. You, as a scriptwriter, may have an idea, develop it and present the story to the marketer to invest in."

commenting on the similarity of most scripts in Nollywood, he remarks that storytelling is an open art where storytellers approach stories from different angles, though they may have the same subjects. Drawing from his literary background, he says that dramatic theories, right from Aristotle, of characterization, the unities, hubris, catharsis, subject matter, etc. have not changed much, underlying a degree of conformity in arts. "Storytelling is all about opinion, and you can't stop anybody from offering his own opinion on a storyline," he admits.

For a moment, his eyes rivet on the television in a corner. His favourite team, Arsenal, is getting a good hiding by Bolton Wanderers in the premiership, and it is quite traumatic for him. He shakes his head at another bungled opportunity by Emmanuel Adebayor, the Togolese Arsenal player, and grumbles: "Why is Bolton always giving Arsenal problem?"

He concedes after the interlude that ours is not wholly a literate society, and issues that dominate daily discussions are football, women, religion and politics. These reflect in the taste of the Nollywood audience. What explanation can he offer for the recurrence of a select group of star Nollywood thespians in Nigerian movies? To him, this group poses little or no problems to producers during shooting. Also, the audience expresses preference to films they appear in. "As a producer, once you use these known faces in a film, the rate of success of that film is higher. "Sometimes if you risk a new face on a good story, at the end of the day, it's a big loss to the marketer," he explains.

The growing significance of Nollywood to the art and entertainment industry underscores the theme of the 24th ANA Convention in Kano last November, "Literature and the Developing Film Industry". Hyginus Ekwuazi, former Managing Director/CEO Nigerian Film Corporation, Jos, in his lecture, "To the Movies go- Everything Good will come," noted that the contribution of Nigerian literature to the growth of Nollywood has been insignificant.

According to Ekwuazi, The creative collaboration between the industry and Nigerian literature obviously died with the cine. The industry as it presently configured has absolutely no need for ANA and its members – whom it no doubt regards as part o f the cognoscenti, in spite of whom its films are made. ANA cannot be honest without admitting that its contribution to the Nigerian home video is exactly minus zero. And so we search the Nigerian literature its bite: the endless creative experimentation with form and technique; the creative extension of the borders of narrativity, and that voice empowered by indignation and sympathy.

Countering Ekwuazi's unflattering comments on ANA members vis-à-vis their contribution to Nollywood, Ebereonwu stops short of saying that he got hold of the wrong end of the stick, stressing that scriptwriters, like Reginald Ebere, T. Chidi, Emeka Obasi and himself, who write most of the scripts in Nollywood, are all ANA members. Above all, "If you go through their scripts, you will see mature arguments and dialogues, beautiful characterization, powerful storyline, etc."

The world of make-believe and the solitary world of the writer are not far removed, which is not to say that they are the same. "A filmmaker makes his film for now, but an author does not care much about the time his audience reads him, whether in ten year's time of the next twenty years. Most of the time, when you see a book that has been adapted to films, they are not the same as a film scripts. A book is more detailed, but a film is just for two hours," he says of both arts.

The dearth of Nigerian literary classics adapted to films has often raised a question mark on the competence of Nollywood. Achebe's Things Fall Apart, which was adapted in the 1980s, remains the only significant literary classic that is available in the market, though Festus Iyayi's Violence has been adapted, it has yet to enjoy noticeable airtime.

"The Nigerian book industry started developing during the colonial days. The film industry is a recent development. So, most of the book," he says, "do not incorporate what the film industry requires. "These writers wrote at a time there was no possibility of making movies out of them." He also says that most writers writing literature now know little or nothing about the movie, and so do not write with an eye for the industry.

Is he going to keep sealed lips over his weird dress code that often causes a stir in the literary meetings? Not Ebereonwu. "It's a matter of choice. And he is aware that "in a world where people are used to copying what everybody is doing, they are bound to see me as a radical". But he doesn't care because "all the changes in the world are not brought about by people who behave like their grandfathers."

His 2004 collection of poems entitled Unpublishable Poems has some absurd dimensions to it, placing the poet inches to an iconoclast.

"Poetry and scriptwriting meet each other in the level of condensation," he resumes, just as he says the latter shares the same narrative motifs with the novel. What Nollywood is doing right that the writer's community is not doing so, in his view, is in the area of carrying the audience along. He declares controversially that the Nigerian writer does not have an audience, while Nollywood does.

"The Nigerian writer doesn't have an audience, but the Nollywood filmmaker panders to an audience. Nollywood tries as much as possible to identify the needs of the audience. It tells the story of the people. Onitsha Market Literature used the same strategy when it started, and some of the pamphlets sold as much as sixty-thousand copies." He notes that when academics entered the business, readership dropped. His next statement may not go down well in some quarters: "When writers dabble in issues the audience doesn't understand, what do you expect?"

A sip of Schweppes washes down the phlegm.

Across the road, a stifled stridor of traffic builds up with steady hums. His metallic voice yawps rage at a section of the Nigerian press for playing the killjoy to the progress of Nollywood. "Most of the things the media say about Nollywood tend to discourage people from patronizing our films, yet they are so much involved in its exploitation." The intensity of "This is bad!" which he voices thereafter registers the extent of his disenchantment with a section of the press.

From his comments, the television houses insist on the broadcasting right of any new film produced in Nollywood once they are approached for adverts. And the filmmaker has no option than to oblige the request. In this way, the TV houses are showing films they have spent no dime on. "Just because of an advert of say N200, 000, they exploit a film produced with more than N4m. Their criticism of the industry is the most annoying.

Their idea of the movie industry is pedestrian. The parameters you use in critiquing a book isn't the same you use in a film. These people should know this," he fumes, echoing the agelong skirmish between the artist and the critic.

Latest News

-

"Be Intentional, Hardworking, And Be Consistent I

"Be Intentional, Hardworking, And Be Consistent I -

"Stop Comparison, Focus On Your Own Goal" - Funke

"Stop Comparison, Focus On Your Own Goal" - Funke -

Woli Agba Sweetly Celebrates Wife On Birthday

Woli Agba Sweetly Celebrates Wife On Birthday -

"I've Not Retired From Music" - Timaya

"I've Not Retired From Music" - Timaya -

"God Punish Steeze" - Bloody Civilian Bemoans Big

"God Punish Steeze" - Bloody Civilian Bemoans Big -

"Sibling Rivalry Is Not Competition, But Inspirati

"Sibling Rivalry Is Not Competition, But Inspirati -

"I Can't Be Sexually Committed To Only One Person

"I Can't Be Sexually Committed To Only One Person -

"After Touring All 36 States, I'm Filled With Not

"After Touring All 36 States, I'm Filled With Not -

"Thank You For Being An Amazing Part Of My Family

"Thank You For Being An Amazing Part Of My Family -

"This Year Is Like No Other" - Media Personality,

"This Year Is Like No Other" - Media Personality,